Testing Adobe Super Resolution -

How Good Is It with Older RAW Files ?

Brad Nichol

Almost all the known Photography Punditry Suspects (PPS) have been falling over themselves to espouse the goodness of Adobes’ new Super Resolution option. Office Chair Guy Photographers (OCGPs) all over are currently geeking out applying Super Resolution to the 50mp plus images from their high-end cameras and pushing headlong into the esoteric realm of 200+ megapixels. The results are impressive, but few situations demand such resolution even within the professional photography world.

In my opinion, the real benefit of Super-Resolution tool is to breathe new life into older generation cameras in the 12 to 24mp range by increasing the potential print sizes or expanding your crop options. You can also achieve good results by Super Rezzing even older images from 6 megapixel DSLRs, as you will see from my examples. I doubt many people wish to persist in actually using such ancient museum pieces these days.

Super Resolution seems to generally achieve this goal and has given me cause to re-evaluate my camera choices going forward and poses a new question, do I really need that hi-res system upgrade?

Consider this, I have three 16-megapixel cameras, 2 MFTs and one APSC mirrorless and a very serviceable 24mp full-frame Sony DSLR plus around 35 lenses to go with them, don’t mention this to my wife. A change to a new high-res full-frame mirrorless set-up would involve some serious money if I wanted to maintain the same utility score. Heck, I could buy another new motorbike, a nice 2nd hand car or take an overseas holiday for that sort of cash, maybe all three if I really lashed on the high end of the gear spectrum.

I am not saying that Super Resolution is perfect. However, tests over the past weeks using files from my 16 and 24mp cameras have confirmed I can easily give all my gear a new lease on life, without really trading much of anything away. Realistically my case for a big-dollar upgrade has fallen into disarray, the advantages are diminishing. Since I am not involved in shooting sport or extreme low light photography, I cannot really claim the improved high ISO performance of the newer kit as a deal sealer.

Do you have an older 16 to 24 mp DSLR or mirrorless camera? There must be millions of perfectly useable older cameras, many of which are fine performers and are probably more limited by their user capability than any inbuilt technical deficiency. Likewise, there's a large pool of high-end APSC lenses that are being sacrificed cheaply on the altar of full-frame hi-res frenzy.

Take any good 16/24mp APSC DSLR and a good f2.8 zoom, throw in better than average operator skills, stir in some Super Resolution and you might get results that for all intents and practical purposes are just a good as those achieved with a fancy new hi-res FF rig.

Yep, there is a pretty solid market out there in Photography land for this Super Resolution stuff, if it performs as it promises.

So How Much Extra Resolution Do You Get?

I find it hard to make a direct comparison between resolution levels. Start with a camera that's available in multiple resolution versions, like the Sony A7 series. Shoot the same scene, ideally a very detailed landscape, Super Res the files and downsize the images as needed so they all match the output resolution of the top A7 model. I’d love to see this comparison made using a wide array of subject matter and ideally the final results viewed in printed form.

The seat of my pants interpretation of 16mp files is the output looks very similar to what I would expect from a camera of around 30 to 42 megapixels. A 42-megapixel image is around 8000px on the longest side, so working at a resolution at 300 PPI you could expect to make a print of 27 inches instead of 16 inches derived from the 16Mp original file, a rather handy improvement.

Technically a 16mp file renders a 64mp output, the results are not what I'd expect from a 64mp camera, though the improvement is still significant and worthwhile.

Lower resolution files appear to give the largest proportional improvement. My test with the 6Mp 300D Canon files resulted in an output that was vastly better than the original, 10Mp Canon 40D files result in a bit less of a proportional improvement and 16mp files less again. I assume that results for high res-cameras would show an improvement over the donor files but far less dramatically than with lower resolution cameras. There may be other limiting factors with the high-res camera files, as you increase the megapixel count you definitely bump up against the limitations of your lenses. Additionally, as pixel size shrinks, diffraction has an increasing impact on the apertures available to obtain sufficient depth of field for landscape and macro shots. Note also that lenses for larger formats do not resolve as well per mm as those optimised for smaller formats, consider how much resolution an iPhone lens offers in DNG capture despite the sensors tiny size. We may soon have full-frame sensors of 100mp, they are unlikely to produce anything like double the resolved detail of a 50 or even 24mp sensor of identical physical dimensions and lens performance will become an even more significant factor than it currently is.

Looking Forward and Thinking Sideways

Smartphone manufactures are currently taking two paths for optimising resolution.

One shoot at very high resolutions and then down-scaling the image into the 8 to 12 megapixels range.

Two, image stacking using a 12mp or similar sensor, then use AI and other clever processing tricks to render out an optimal 12 mp frame.

Both of the above approaches work well and also offer some insight into alternative pathways for regular cameras.

There is most likely a practical limit to how much more detail can be made by more megapixels. Physical factors will come into play including, lens quality, diffraction, user stability, focus accuracy, mechanical vibration, depth of field limits and probably others I've not thought of. Super Resolution or some similar Ai process could well be the pathway to extending resolution beyond the above limits and defying physics.

Higher megapixel counts are not always desirable or optimal. All things being equal if we take a lower resolution sensor of a given size and compare it to a higher resolution sensor of the same dimensions, the lower resolution version will generally exhibit less image noise and improved low light performance.

Camera makers don't leverage the above capability because they have continued to develop higher megapixel sensors for APSC and FF in a race for ever higher specs and numbers supremacy. Marketing potential often rules practicality in corporate decisions making.

Sony could have continued to develop the rather good 16mp sensor found in many older DSLRs and Mirrorless cameras to produce lower noise versions and improvements in other aspects of performance. Instead, Sony upped the ante to 24mp sensors across the board, selling better 16mp versions probably likely lacked marketing appeal.

Kudos however to Sony for what they have done with the A7 series where you can actually choose the lower megapixel version for optimal low light capability.

Pause for a moment and consider this, what if camera makers took a leaf out of the smartphone playbook and went all out on maximum performance for 16mp -20mp sensors and then relied on AI and stacking methods to bridge the resolution gap. Such an approach could be technically ideal, and users could avoid the pain of having to buy ever more expensive lenses. Scrub that idea, such an approach would go against the grain for camera makers who generally want to sell you the latest and greatest.

Super Resolution offers the same approach that smartphones have leveraged over the past 5 years, the gains of AI and clever processing are seen every day right there on our smartphone screens. It seems logical that regular camera makers will have to move towards Ai methods or become consumed in the tidal wave of smartphone imaging technology.

What Are The Pitfalls?

First, Super-Resolution works with any file though it is really intended for RAW files. My tests show the benefits with JPEGs and HEIFs are marginal at best and usually not worthwhile. JPEG compression eats away the fine textural detail and deprives the Super-Resolution algorithm of the information needed to work efficiently.

Second, the way files respond to the tool is very dependent on the camera used, mainly due to the strength of the anti-aliasing (AA) filter. The ISO selected and the lens attached to the camera also interact with the capability of the tool. Your results will likely vary from mine, you will need to do some tests with your own gear to see if Super Resolution is super for you.

And third, the tool has no embedded options, but the settings applied to the RAW file before using Super Resolution has a massive effect on the final output appearance. Again, your results could be somewhat tainted by poor RAW process setting choices.

In short, if you adjust the image so it looks sharp and fully finished on-screen before applying Super-Resolution you will almost certainly end up with an over-cooked final result.

Let’s dive a little deeper…..

Many older cameras had quite strong aliasing filters covering the sensor to prevent moire’/aliasing effects and also to improve small-scale false colour reproduction problems. The downside is that strong AA filters limit the fine detail and texture you can retrieve from the raw files.

Aliasing/moire’ issues only impacted on a limited subset of photos, typically those with repeating patterns and textures, even then, moire’ didn’t show up as a significant issue in most photos, it really depended on how close you were to the object in question.

So we had an issue that sometimes messed with our photos and camera makers solved it by turning all your photos to mush, not exactly an ideal solution! Fortunately, the heavy-handed AA filtering many makers embraced eventually gave way to a more conservative approach.

Increasing the resolution of the sensor reduces the need for the filtering in the first place, many camera makers deleted the filter altogether, which may be why many of the Super-Resolution tests with hi-res cameras resulted in significant artefact problems.

I expect that without the AA filter, false colour problems start to rear their ugly heads. Many of the test shots I have seen on the web were littered with ugly random colour specks that appear unrelated to the actual subject colours.

My tests indicate that the damage caused by over-strong AA filters really cannot be unwound by Super-Resolution. The good news is that many older 16 megapixel cameras have very mild AA filters, for example, many of the Sony NEX series models and the later Olympus and Panasonic MFT bodies. These mild-filtered cameras make great candidates for some Super-Resolution fun. You should probably do some online checking to find out if your particular camera is cursed with an overly strong or missing AA filter.

Lens Issues?

Lens choice definitely impacts the results, Super-Resolution will not help much if the lens is a soft marshmallow mess of marginal optics.

I tried a few files from my old 6mp Canon 300D shot using the 18-55mm Canon Kit lens of the day (around 2002-2004). That lens is only marginally better than the bottom of a dirty coke bottle, a real stinker, so it is probably unfair to expect much. I found the scaled-up results using my favourite raw conversion app, (Iridient Raw Developer) with some well-chosen parameters and demosaicing algorithms was superior to Super Resolution. So, if you’re looking for a magic pill to rid you of muddle-n-mush, sorry, it is not going to happen.

On the other hand, 300D shots taken using a Tampon 28-70 f 2.8 responded very nicely indeed, producing results that looked close to those obtained from a 16mp sensor camera.

Oddly, testing reveals some lenses are actually too contrasty to work well with Super Resolution, mainly those exhibiting very high micro-contrast. The problem seems to be even with the input parameters dialled back, sharpness turned off etc, the output files show still show harsh artefacts along high contrast edges. These files don’t edit near as well as those derived from the less contrasty lenses.

Diglloyd has some examples here of the sort of effects I’m referring to.

https://diglloyd.com/blog-2021-03.html#20210310_1900-Photoshop-AdobeCameraRaw-SuperRes

Applying Super Resolution to files taken with my Sony NEX5n and 5T using adapted Nikon 35-70 and Micro Nikkor 55mm lenses produced amazing results. These old school legacy lenses are low contrast yet still produce high levels of fine detail and seem well matched to the needs of Super-Resolution perfectly.

I got very similar results using the same lenses on the Olympus EM 5 mk 2 despite the smaller size of the M4/3 sensor.

Even better were the results I obtained from test shots taken using the 55mm Micro Nikkor mounted onto the Sony NEX 5N via the Viltrox Speed Booster. Trust me, this combo really rocked, you can read a very detailed test of the Viltrox adapter I did a few years ago here.

Test shot taken for a previous article using Nikon legacy lenses on a Viltrox Speed Booster. The camera was the 16mp Sony NEX 5n and the lens a 30yr old Micro Nikkor 55mm f2.8. The top crop is the non Super Resolution version and the bottom with Super Resolution. The lens/camera/booster combo is a great match for Super Resolution with the final file giving 40mp camera files a run for their money.

Image noise can factor into the mix and make for ugly results, if you think those noisy old files shot at 1600 ISO plus are going to sing like a canary, nope, they won’t. But you can improve the general look by paying careful attention to the noise reduction settings applied to the image before processing with Super Resolution.

I found no noise-related issues at all with any files that were properly exposed at ISO 400 or below, 800 ISO files would probably also be acceptable, especially if you do a little noise reduction tweaking after the files are converted from RAW.

Finally, when you get down to the pixel level, different camera raw files will display different textural qualities, if you zoom into 400% view you'll see what I mean.

Sometimes the textural quality interacts with the interpolation method producing ugly results, and you guessed it, the Super-Resolution tool amplifies that ugliness. To limit harsh textural issues turn the texture control found under the basics tab down, way down.

To sum it up, your results will vary with the camera, lens, ISO and in particular the input settings you dial into Camera Raw before you access the Enhance/Super Resolution tool and click Ok. If you manage to hit the sweet spot the results are very nice indeed.

The primary deficit of Super-Resolution is that it’s too easy to end up with artefacts that take the form of jagged edges, hash-like patches and rough patterning, much of this will be limited by having the right input settings as discussed above, but some cameras still produce files far more prone to artefacts than others.

There’s no database out there to tell you what cameras might be problematic, as more people experiment with Super-Resolution there will likely be more anecdotal information on photo forums to guide you.

In particular, you may have issues with repeated patterns, corrugated iron roofing, wire fences, fabrics etc. Areas of very low contrast detail may also fool the algorithms, either producing more mush on a larger scale or weird random hash areas.

Files from cameras having just the right sort of AA filter work best, too weak, and you will get nasty patterns, too strong, you get mush, with little extra detail.

Exposure is also a factor, if your files are exposed so that the highlight details are clipped to white or very close to white they can’t be fully recovered at the small scale level, the resulting images will look crunchy and unattractive, a bit like you went overboard with the sharpening amount and radius in Photoshop.

Super Resolution and Pixel Shifted Files

How does Super Resolution work with pixel shifted Hi-Res files? I tried it out on some 64mp files from my Olympus EM5 Mk2. These files worked well with Super Resolution, producing images devoid of the artefacts seen in the regular files. I assume that pixel shifting provides full-colour detail in all pixel positions, better suiting the needs of Super-Resolution and thus avoiding false colour problems.

I noticed on a couple of files that diagonal lines occasionally produced jaggies, it's unlikely you would see these in a large print. If you were concerned with these minor defects you could fix them with selective blurring in Photoshop.

Since there are now many cameras offering pixel shift shooting, Super-Resolution is a neat trick for those rare occasions you absolutely need to produce final prints of enormous size or perhaps perform a super extreme crop. Bear in mind, resulting file sizes will break the 200 plus megapixels barrier, output at 16 bits and files will break into 400Mb plus territory. Older computers will start to choke pushing these large files around, put it this way, my 3 yr old iMac with 32Gb of Ram didn't exactly run the 10-second hundred-meter dash on 400Mb files.

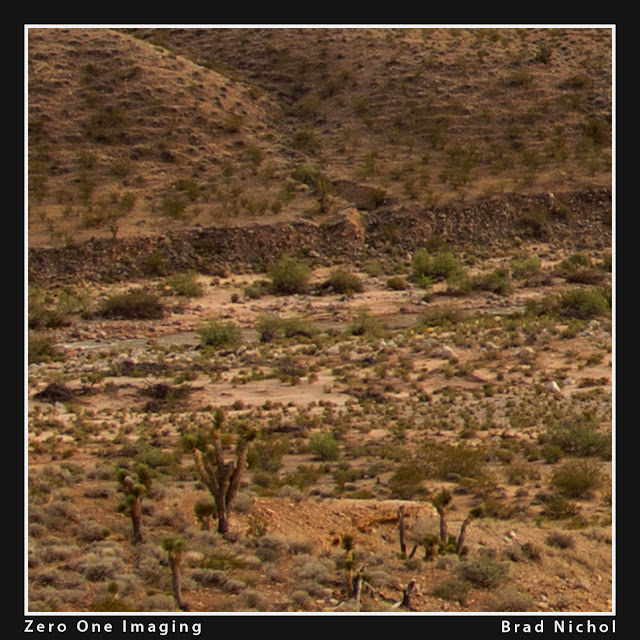

Monochrome images live and breathe by virtue of fine textural detail and contrast, Super Resolution can be used to upsize images that will work well with added noise and textural sharpening. This image was taken in Zion National Park using a 16mp Sony NEX5n and an old school Nikon 35-70 f3.5 zoom, it works like a charm with Super Resolution.

Practical Uses

There are several reasons why you might want to increase the resolution of your files:

You want to print larger sizes than your camera is natively suited for.

You have lots of older low res RAW files you want to print to reasonable sizes.

You wish to crop the image tightly.

You lack a telephoto lens and need to obtain the reach digitally.

You want more detail, perhaps even for a regular-sized image.

You don’t have a macro lens but you want to get in closer.

You do have a macro lens but getting in closer limits the depth of field too much for your needs, so you need a work-around.

You want to apply noise filters or carry out some fancy sharpening processes, both of which work better if you have more pixels.

I am sure there are others reasons for using Super-Resolution that not listed.

A lovely grouping of rocks taken at Arthurs Pass in NZ, the camera was a Canon 300D with a Tamron 28-75mm f2.8, despite being a mere 6mp the Super Resolution image came up very nicely. I would judge it as close to being equal 16mp capture. See the crop below, some noise/grain has been added for effect.

Can You do Better By Just Upsizing in Photoshop?

Fair question, in most cases, no. Super-Resolution will usually create extra detail and texture whilst avoiding the mush that often results when using the regular resize option in Photoshop.

On the other hand, you can get very similar results (without artefacts) by using a specialised RAW convertor. Some of the more sophisticated RAW conversion applications provide custom upsizing and demosaicing options, Iridient Developer is an example.

To use these advanced RAW Converter tools you will need a good handle on exactly what the advanced processing options do, you will definitely need to carry out some tests with your particular camera files.

Can You Use Super Resolution Beyond 2 Times?

Super-Resolution is a one-trick pony, it will only make the image twice as large on both dimensions, thus you get 4 times as many pixels as the original photo. Should you want less enlargement you will have to run SR and then downsize in Photoshop.

What about going bigger?

Yes, you can, but it involves a messy workaround. I have taken the time to test this for you, which confirmed two things. The process won't create any additional detail and it will increase the artefact problems.

If you absolutely need a larger image run the file through SR as normal then upsize in Photoshop using the regular resize tool

Summing Up

Super Resolution is certainly worth trying, it might just be the answer to your longing for more resolution without the cost attached to such an esoteric pursuit. There might also be a hidden benefit in choosing not to upgrade your gear, the time and effort needed to get your head around a new camera and lenses can stifle your creative side. Shooting is far more fluid and unrestrained when your gear fits you like a nice old comfy pair of shoes.

Super-Resolution works well at present but has significant issues with artefacts which can be limited considerably by getting your input settings right, however, we should not need to concern ourselves with this in the first place.

I expect that Adobe will refine the tool over the next two years, and despite the issues, Super Resolution does point the way towards the future of photo processing.

Super Resolution is not a magic pill, my socks have not been blown clean off by it, the hype exceeds reality in my opinion but it remains a useful tool. I suggest you try Super Resolution on some images and see what you think.